| Real Name | Ethan Green Hawke |

|---|---|

| Net Worth 2026 | $55 million USD |

| Birthday (Year-Month-Day) | 1970-11-6 |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Actor, Writer, Director |

| Height | 1.79 m or 5 ft 10 inches |

| Weight | 82 kg or 181 pounds |

| Marital Status | Married (Ryan Hawke) |

| Ethnicity | English, Scottish and Scots-Irish (Northern Irish) |

| Education | Carnegie Mellon University |

| Kids | 4 |

| Kids Names | Maya, Levon Roan, Indiana, Clementine Jane |

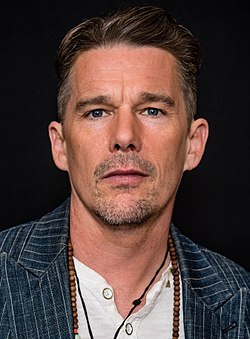

Ethan Hawke | |

|---|---|

Hawke in 2025 | |

| Born | Ethan Green Hawke November 6, 1970 Austin, Texas, US |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1985–present |

| Works | Full list |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 4, including Maya and Levon |

| Awards | Full list |

Ethan Green Hawke (born November 6, 1970) is an American actor, author, and filmmaker. Over a four-decade career on both stage and screen, Hawke has become known for his versatility across a wide range of roles and acclaimed collaborations with director Richard Linklater. Prolific in both independent films and blockbusters, he has received numerous accolades including a Daytime Emmy Award, in addition to nominations for five Academy Awards, three Golden Globe Awards, two British Academy Film Awards, and a Tony Award.

Hawke made his film debut at age fourteen in Explorers (1985) and gained recognition for starring in Dead Poets Society (1989). He established himself as a leading man with the films Reality Bites (1994), Gattaca (1997), and Great Expectations (1998). Hawke received Best Supporting Actor Oscar nominations for his roles in the crime thriller Training Day (2001) and the coming-of-age drama Boyhood (2014), the latter also garnering him BAFTA and Golden Globe nominations. He was Oscar-nominated twice for screenwriting two films from the Before trilogy (1995–2013), in which he also starred. He earned Best Actor nominations at the Oscars, BAFTAs, and Golden Globes for portraying lyricist Lorenz Hart in the biopic Blue Moon (2025).

Hawke garnered commercial success with Sinister (2012), The Purge (2013), The Magnificent Seven (2016), and the Black Phone films (2021–2025), and was praised for Maudie (2016) and First Reformed (2017). He directed the films Chelsea Walls (2001), The Hottest State (2006), Blaze (2018), and Wildcat (2023), as well as the documentaries Seymour: An Introduction (2014), The Last Movie Stars (2022), and Highway 99: A Double Album (2025). He portrayed abolitionist John Brown in the miniseries The Good Lord Bird (2020), for which he received a Golden Globe nomination, and appeared as Arthur Harrow in the Marvel miniseries Moon Knight (2022).

Hawke has appeared in many theater productions. He made his Broadway debut in 1992 in Anton Chekhov's The Seagull and was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Featured Actor in a Play in 2007 for his performance in Tom Stoppard's The Coast of Utopia. In 2010, he was nominated for the Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Director of a Play for directing Sam Shepard's A Lie of the Mind. Divorced from actress Uma Thurman, he has been married to Ryan Shawhughes since 2008; he has two children from each marriage, including actors Maya and Levon Hawke.

Early life

Ethan Green Hawke was born in Austin, Texas, on November 6, 1970.[1] His father, James Hawke, was an insurance actuary, while his mother, Leslie (née Green), was a charity worker and teacher.[2][3][4] Hawke's parents were high school sweethearts from Fort Worth, Texas, and married when his mother was seventeen.[5] Hawke was born a year later, while both of his parents were attending the University of Texas in Austin. His parents separated and later divorced in 1974, when he was four years old.[2][6]

After his parents separated, Hawke was raised by his mother.[7] Hawke recalled first donning different personas as a child trying to please his parents, by pretending to be an "artistic, literary, conscientious political thinker" for his mother and a well-mannered, religious football lover when visiting his father.[4] Hawke and his mother moved several times before settling in Brooklyn, where he attended the Packer Collegiate Institute.[7][8] Hawke often shifted his personality to fit in with different groups of peers that he encountered in their moves.[4] When Hawke was ten or twelve, his mother remarried and the family relocated to West Windsor Township, New Jersey.[7][9] There, he attended West Windsor Plainsboro High School[10] before transferring to the Hun School of Princeton, a boarding school from which he graduated in 1988.[11][12] Around this time, Hawke volunteered with his mother's organization, the Alex Fund, a charity that supported educational opportunities for underprivileged children in Romania.[4]

In high school, Hawke aspired to become a writer while also developing a strong interest in acting.[13][14] During his time at the Hun School, he also studied acting at the McCarter Theatre, located on the Princeton University campus.[15] He made his stage debut at age thirteen in the theater's production of George Bernard Shaw's Saint Joan.[4] He later performed in his high school's productions of Meet Me in St. Louis and You Can't Take It with You.[15] After graduating, Hawke continued to study acting at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh but left after being cast in Dead Poets Society (1989).[16] He later enrolled in New York University's English program for two years before leaving to pursue acting full-time.[14]

Career

1985–1993: Early years and breakthrough

With his mother's permission, Hawke attended his first casting call at age fourteen and was cast in Joe Dante's Explorers (1985), playing a misfit schoolboy alongside River Phoenix.[17][18] Although the film received positive reviews,[19] it performed poorly at the box office, leading Hawke to step away from acting for a time after its release. He later described the experience as difficult to handle at such a young age, remarking, "I would never recommend that a kid act".[16] In 1989, Hawke had his breakthrough role as a shy student in Peter Weir's Dead Poets Society.[20][21] The film was critically and commercially successful and won the BAFTA Award for Best Film.[22] Reflecting on the impact of its success, Hawke later said, "I didn't want to be an actor and I went back to college. But then the film's success was so monumental that I was getting offers to be in such interesting movies and be in such interesting places and it seemed silly to pursue anything else."[18] After filming Dead Poets Society, he auditioned for his next project, the comedy-drama Dad (1989), and settled in New York City due to its prominent theater industry and variety of opportunites.[23][24]

In 1991, Hawke co-founded Malaparte, a Manhattan-based theater company that operated until 2000.[25][26] His first leading role came with Randal Kleiser's film White Fang (1991), an adaptation of Jack London's novel of the same name, in which he portrayed a young Klondike gold prospector who befriends a wolfdog.[27][28] A writer for The Oregonian appreciated how he kept the film from "being ridiculous or overly sentimental",[29] while Roger Ebert praised how he was "properly callow at the beginning and properly matured at the end";[30] Hawke himself later called it the "single best experience of my acting life".[31] In A Midnight Clear (1992), his character leads a group of American soldiers during World War II, tasked with capturing a small squad of German troops stationed in the Ardennes forest in France.[32] Hawke made his Broadway debut in 1992, portraying the playwright Konstantin Treplev in Anton Chekhov's The Seagull at the Lyceum Theater in Manhattan.[33] He then played Nando Parrado, one of the survivors of the Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 crash in the Andes, in the survival drama Alive (1993), adapted from Piers Paul Read's 1974 non-fiction book.[34]

1994–2000: Established leading man

Hawke's next role was in the Generation X drama Reality Bites (1994), in which he portrayed a disaffected slacker who mocks the ambitions of his love interest, played by Winona Ryder.[35] Ebert liked his "convincing and noteworthy" performance, writing that "Hawke captures all the right notes as the boorish Troy".[35] Caryn James observed that his "subtle and strong performance makes it clear that Troy feels things too deeply to risk failure and admit he's feeling anything at all".[36] The film did moderately well at the box office, grossing $41 million on a budget of $11 million.[37][38] Hawke starred in Richard Linklater's Before Sunrise (1995), the first installment of the Before film trilogy.[39] He portrayed a young American man who meets a young French woman—portrayed by Julie Delpy—and they both disembark in Vienna.[40] The reception for the film and Hawke's performance was positive, with the former receiving a 100 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes.[41]

Hawke directed the music video for Lisa Loeb's US Billboard Hot 100 number-one single "Stay (I Missed You)"; Loeb was then a member of Hawke's theater company.[42][43] Spin magazine named the video its Video of the Year in 1994.[44] Hawke appeared in a 1995 production of Sam Shepard's Buried Child, directed by Gary Sinize at the Steppenwolf Theater in Chicago.[45] He published his first novel, titled The Hottest State, in 1996, which tells the story of a love affair between a young actor and a singer. He described writing the book as both the "scariest [... but also] one of the best things I ever did."[18] Entertainment Weekly said that Hawke "opens himself to rough literary scrutiny in The Hottest State. If Hawke is serious [...] he'd do well to work awhile in less exposed venues."[46] The New York Times thought Hawke did "a fine job of showing what it's like to be young and full of confusion", concluding that The Hottest State was ultimately "a sweet love story".[47]

"Writing the book had to do with dropping out of college and with being an actor. I didn't want my whole life to go by and not do anything but recite lines. I wanted to try making something else. It was definitely the scariest thing I ever did. And it was just one of the best things I ever did."

Hawke called his script in Andrew Niccol's science fiction film Gattaca (1997) "one of the more interesting" ones he had read in "a number of years".[48] In it, he played the role of a man who infiltrates a society of genetically perfect humans by assuming another man's identity.[49] Ebert called him a good choice for the lead role, stating that he "combin[es] the restless dreams of a 'Godchild' with the plausible exterior of a lab baby".[49] Alongside Gwyneth Paltrow and Robert De Niro, he starred in Great Expectations (1998), a contemporary film adaptation of Charles Dickens's 1861 novel of the same name, directed by Alfonso Cuarón.[50] Hawke criticized the film's time of release, stating that "nobody gave a shit about anything but Titanic for about nine months after [...] particularly another romance".[51] He collaborated with Linklater once again on The Newton Boys (1998), based on the true story of the Newton Gang.[52] The film saw generally negative reception; Rotten Tomatoes' consensus said that the "sharp" cast made up for "the frustrations of a story puzzlingly short on dramatic tension".[53]

In 1999, he starred as Kilroy in the Tennessee Williams play Camino Real at the Williamstown Theater Festival in Massachusetts.[54] That year, Hawke starred in Snow Falling on Cedars, adapted from David Guterson's novel of the same name. Set in the 1950s, he played a young reporter who covers the murder trial of a fisherman.[55] The film received a tepid response,[56] with Entertainment Weekly commenting that "Hawke scrunches himself into such a dark knot that we have no idea who [his character] Ishmael is or why he acts as he does".[57] Hawke's next film role was in Michael Almereyda's Hamlet (2000), in which he played the titular character. The adaptation set William Shakespeare's play in contemporary New York City, a choice Hawke said made the story feel more "accessible and vital".[58]

2001–2006: Training Day and further Linklater films

In 2001, Hawke appeared in two more Linklater films: Waking Life and Tape, both critically acclaimed.[59][60] In the animated Waking Life, he shared a single scene with former co-star Delpy continuing conversations begun in Before Sunrise.[61] The real-time drama Tape, based on a play by Stephen Belber, took place entirely in a single motel room with three characters played by Hawke, Robert Sean Leonard and Uma Thurman.[62] Hawke then portrayed rookie cop Jake Hoyt alongside Denzel Washington, as part of a pair of narcotics detectives from the Los Angeles Police Department spending a day in the gang-infested neighborhoods of South Los Angeles, in Training Day (2001).[63][64] The film saw favorable critical reception;[65] Paul Clinton of CNN described Hawke's performance as "totally believable as a doe-eyed rookie going toe-to-toe with a legend [Washington]".[66] Hawke later called Training Day his "best experience in Hollywood".[18] His performance earned him nominations for the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Supporting Role and the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.[67][68]

Hawke explored several projects outside of acting in the early 2000s. He made his directorial debut with Chelsea Walls (2002), an independent drama about five struggling artists living in New York City's Hotel Chelsea.[69] That same year, he published his second novel, Ash Wednesday (2002), which appeared on The New York Times Best Seller list.[70] Centered on an AWOL soldier and his pregnant girlfriend,[18] the novel earned praise from critics. The Guardian described it as "sharply and poignantly written [...] an intense one-sitting read",[71] while James noted that Hawke showed "a novelist's innate gifts [...] a sharp eye, a fluid storytelling voice and the imagination to create complicated individuals", though it found him "weaker at narrative tricks that can be taught".[72] Returning to Broadway, he played Henry Percy (Hotspur) in Jack O'Brien's 2003 production of Henry IV.[73] Ben Brantley, writing in The New York Times, opined that Hawke's interpretation of Hotspur might be "too contemporary for some tastes", but allowed "great fun to watch as he fumes and fulminates".[74]

Hawke returned to film in 2004 with two releases: the psychological thriller Taking Lives and the romantic drama Before Sunset. Upon release, Taking Lives received broadly negative reviews,[75] though Hawke's performance as a serial killer who takes on the identities of his victims was favored by a critic from the Star Tribune, who said that he played the "complex character persuasively".[76] He then reunited with Linklater for Before Sunset, the second installment of the Before trilogy.[77] Co-written by Hawke, Linklater, and Delpy, the film follows a young man and woman who reunite in Paris nine years after meeting in Vienna.[78] A Hartford Courant writer remarked that the screenwriting collaboration between the three "[kept] Jesse and Celine iridescent and fresh, one of the most delightful and moving of all romantic movie couples".[79] Hawke called it one of his favorite films, a "romance for realists".[80][81] Before Sunset was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.[82]

Hawke starred in the 2005 action thriller Assault on Precinct 13, a loose remake of John Carpenter's 1976 film of the same name with an updated storyline.[83] He played a police sergeant who must band together with criminals to defend a police precinct from a siege by corrupt cops.[84] While numerous critics found it inferior to the original,[85] they enjoyed Hawke's performance,[86] with Jami Bernard from New York Daily News stating that Hawke and co-star Laurence Fishburne made the film work, "supported by a mostly strong cast".[87] In 2006, he directed his second feature film, The Hottest State, based on his 1996 novel of the same name.[88] It saw poor reception from critics, largely for being too self-conscious and overly pretentious.[89] From November 2006 to May 2007, Hawke starred as Mikhail Bakunin in Tom Stoppard's trilogy play The Coast of Utopia, an eight-hour-long production at the Lincoln Center Theater in New York.[90] The performance earned Hawke a Tony Award nomination for the Best Featured Actor in a Play.[91]

2007–2012: Continued acclaim

Hawke starred alongside Philip Seymour Hoffman, Marisa Tomei, and Albert Finney in the crime drama Before the Devil Knows You're Dead (2007), the final direction of Sidney Lumet. Hawke prepared for his role by working closely with Lumet during a two-week rehearsal period, which allowed the cast to make creative decisions before filming began. On-set, Lumet intentionally pitted Hawke and Hoffman against each other to heighten the tension.[92][93][94] In Before the Devil Knows You're Dead, Hawke played the younger brother of a debt-ridden broker who entices him into a plan to rob their parents' bank, but the scheme goes awry.[95] USA Today's Claudia Puig deemed the film "highly entertaining", describing Hawke and Hoffman's performances as excellent,[96] while Peter Travers, writing for Rolling Stone, stated that Hawke "[dug] deep to create a haunting portrayal of loss".[97]

In November 2007, Hawke directed Things We Want, a two-act play by Jonathan Marc Sherman, for the artist-driven off-Broadway company the New Group.[98] New York praised Hawke's "understated direction", particularly his ability to "steer a gifted cast away from the histrionics".[98] In Brian Goodman's crime drama What Doesn't Kill You (2008), Hawke played the childhood friend of Mark Ruffalo's character, who both become involved in crime in their South Boston neighborhood and scheme a heist to escape poverty.[99] Peter Brunette—in The Hollywood Reporter—named Hawke's performance a "personal best",[100] and the New York Times critic Manohla Dargis wrote that he "holds [the viewer] with a physically expressive performance that telegraphs each byroad of his character's inner world".[99] Hawke appeared in two features in 2009: New York, I Love You, a romance film comprising twelve short films;[101] and Staten Island, a crime drama in which he co-starred alongside Vincent D'Onofrio and Seymour Cassel.[102]

To prepare for his role as a vampire hematologist in the science fiction horror film Daybreakers (2009), Hawke studied "the greats" of past cinematic vampire performances, including Willem Dafoe's portrayal in Shadow of the Vampire (2000).[103][104] He traveled to Australia to film Daybreakers, which was directed by The Spierig Brothers.[105] The film fared well both critically and commercially, grossing $51 million on a $20 million budget.[106][107] Hawke's next role was in Antoine Fuqua's Brooklyn's Finest, in which he portrayed a corrupt narcotics officer.[108] Although the film—released in the US in 2010—opened to mediocre reception,[109] his performance garnered praise from critics, including a New York Daily News reviewer who remarked, "Hawke—continuing an evolution toward stronger, more intense acting than anyone might've predicted from him 20 years ago—drives the movie."[108]

In January 2010, Hawke directed his second play, Sam Shepard's A Lie of the Mind, on the New York stage.[110] It marked the first major off-Broadway revival of the play since its 1985 debut.[111] Hawke was attracted to the play's exploration of "the nature of reality" and its "weird juxtaposition of humor and mysticism".[112][111] In his review for The New York Times, Brantley lauded the production's "scary, splendid clarity" and praised Hawke for eliciting a performance that "connoisseurs of precision acting will be savoring for years to come".[113] Entertainment Weekly commented that although A Lie of the Mind "wobbles a bit in its late stages", Hawke's "hearty" revival managed to "resurrect the spellbinding uneasiness of the original".[114] The production garnered five Lucille Lortel Award nominations, including one for Outstanding Revival,[115] and earned Hawke a Drama Desk Award nomination for Outstanding Director of a Play.[116]

In the 2011 television adaptation of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick, Hawke played the role of Starbuck, the first officer to William Hurt's Captain Ahab.[117] He then starred opposite Kristin Scott Thomas in Paweł Pawlikowski's The Woman in the Fifth, a "lush puzzler" about an American novelist struggling to rebuild his life in Paris.[118][119] In 2012, Hawke appeared in the horror genre for the first time, playing a true crime writer in Scott Derrickson's Sinister, written along with C. Robert Cargill. Before the US release of Sinister, Hawke said that he had previously been hesitant about horror films because they often do not require strong acting performances. However, he mentioned that the producer of Sinister, Jason Blum, with whom Hawke had a background in theater, approached him with an offer involving a script that featured both a "great character and a real filmmaker".[120][121]

2013–2018: Boyhood and career expansion

Hawke reunited with director Linklater and co-star Delpy for the third installment of the Before trilogy, titled Before Midnight (2013).[122] The film follows a couple, he and Delpy's character, who spend a summer vacation in Greece with their children.[123] Before Midnight received critical acclaim,[124] with one from Variety naming the scene in the hotel room "one for the actors' handbook".[125] The film earned Hawke, Linklater, and Delpy another Academy Award nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay.[126] Hawke next starred in the horror-thriller The Purge (2013), set in a future America where all crime is legal for one night each year.[127][128] Despite mixed reviews, the film opened atop the box office on its opening weekend with a $34 million debut.[129][130] In early 2013, Hawke starred in and directed the play Clive, written by Jonathan Marc Sherman and inspired by Bertolt Brecht's Baal.[131]

Hawke prepared for his role as a former racecar driver in Getaway (2013) by attending a one-day driving school at the Mid-Ohio Sports Car Course, where he learned high-performance driving techniques such as 180-degree spins and e-brake maneuvers.[132] The film was critically panned.[133] He played the title role in a Broadway production of Macbeth at the Lincoln Center Theater in late 2013. The Hollywood Reporter critic David Rooney criticized the "disharmonious acting styles led by Hawke's underpowered take on [his] role".[134] Released in mid-2014, Linklater's Boyhood follows the life of an American boy from age six to eighteen, with Hawke portraying his father.[135] The film became the best-reviewed release of 2014 and was named best film of the year by numerous critics' associations.[136][137] Hawke later admitted that the film's widespread acclaim came as a surprise, recalling that when he first joined the project, it felt less like a "proper movie" and more like "a radical '60s film experiment or something".[138] He earned several nominations for his performance, including the Academy Award, BAFTA, Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actor.[139][140][141]

Hawke reunited with the Spierig brothers for the science fiction thriller Predestination (2014), in which he played a time-traveling agent on his final assignment.[142][143] Writing for Vulture, David Edelstein wrote how he enjoyed Hawke's "low-key, solemn, enigmatic" performance.[144] He next reunited with his Gattaca director Andrew Niccol for Good Kill (2014), a contemporary war drama. In his "best screen role in years" according to Rooney, Hawke portrayed a drone pilot grappling with a troubled conscience.[145] He made his documentary debut with Seymour: An Introduction, which premiered at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival.[146][147] The film was conceived after a dinner party attended by both Hawke and its subject, classical pianist Seymour Bernstein. Seymour: An Introduction is a profile of Bernstein, who later said that, although he was normally a private person, he was unable to decline Hawke's request to make the film because the actor was "so endearing".[148]

Hawke had two films premiere at the 2015 Toronto International Film Festival, both of which were well-received.[149][150] In Robert Budreau's drama Born to Be Blue (2015), he portrayed jazz musician Chet Baker, focusing on the artist's turbulent late-1960s comeback and struggle with heroin addiction.[151][152] He also starred in Rebecca Miller's romantic comedy Maggie's Plan as an anthropologist and aspiring novelist, alongside Greta Gerwig and Julianne Moore.[153] That same year, he appeared in the coming-of-age drama Ten Thousand Saints and the psychological thriller Regression opposite Emma Watson.[154][155] In November 2015, Hawke published his third book, Rules for a Knight, written as a letter from a father to his four children reflecting on moral values and personal integrity.[156] In Ti West's western In a Valley of Violence, he played a drifter who seeks revenge in a small frontier town ruled by a ruthless marshal—a performance that critics praised.[157][158]

In 2016, Hawke took on two unpleasant roles in succession, first playing the abusive father of a promising young baseball player in The Phenom,[159] and then the stern husband of Maud Lewis—portrayed by Sally Hawkins—in Maudie. While some critics commended his surprising range, others argued that Hawke was "miscast" as a harsh figure.[160][161][162] He reunited with Training Day director Antoine Fuqua and actor Denzel Washington for The Magnificent Seven (2016), a remake of the 1960 western film of the same name.[163] In the film, Hawke played a former Confederate sharpshooter struggling with PTSD from the American Civil War.[164][165] In the US, the film grossed $34.7 million in its opening weekend, topping the box office.[166] Also in 2016, Hawke narrated the interactive short film Invasion!, which earned him and his co-creators a Daytime Emmy Award for Outstanding Interactive – Original Daytime Content,[167][168] and released his fourth book, Indeh: A Story of the Apache Wars, which chronicles the conflicts between the Apache and the US.[169]

Hawke starred in Paul Schrader's drama First Reformed (2017) as a former military chaplain tormented by the death of his son, whom he had encouraged to join the armed forces, while grappling with the looming threat of climate change.[170][171] Critics, including Slate's K. Austin Collins, praised his performance, calling it "extraordinarily well-tuned" and stating that "every ounce of likability, vulnerability, angry cynicism and ineptitude [in his career] seems to be summed up here".[172] Hawke had two films premiere at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival.[173][174] In Juliet, Naked, a romantic comedy adapted from Nick Hornby's 2009 novel of the same name, he played an obscure rock musician whose eponymous album drives the plot.[175] Blaze, his third direction, is a biographical film about the obscure country musician Blaze Foley and was selected for the festival's main competition.[176]

2019–present: mainstream popularity

Hawke returned to Broadway in the revival of Shepard's True West, which began previews in December 2018, opened in January 2019, and closed two months later.[177] Critics disparaged the lack of synergy between him and co-star Paul Dano.[178][179][180] In 2019, Hawke appeared in Vincent D'Onofrio's feature film directorial debut, The Kid, in which he portrayed a sheriff hunting the outlaw Billy the Kid.[181] Bilge Ebiri said that his "melancholy stoicism" in the role "fail[ed] to convey much of an inner life".[182] Hawke then produced and starred in Adopt a Highway (2019), which received mixed reviews that nonetheless appreciated his performance.[183] He portrayed a failed actor in Hirokazu Kore-eda's first English-language film, The Truth (2019), which opened the 76th Venice International Film Festival.[184] Entertainment Weekly described Hawke as "brilliantly cast",[185] while Alonso Duralde said that he had managed to play an "untalented, struggling" actor "without delving into condescension".[186]

In 2020, Hawke portrayed inventor and engineer Nikola Tesla in the biopic Tesla.[187] For the role, he drew inspiration from both Tesla's own writings and singer David Bowie, who had played Tesla in The Prestige (2006).[187] Amy Nicholson and Richard Roeper observed that Hawke's version of Tesla diverged from other common popular portrayals.[188][189] He and author Mark Richard adapted James McBride's novel The Good Lord Bird (2013) into a 2020 miniseries produced by Blum, with Hawke starring as abolitionist John Brown.[190] Hawke had developed an interest in the American Civil War and its contemporary ramifications while filming The Magnificent Seven and learning about the legal battles about the display of the Confederate flag in South Carolina.[4] He consulted McBride and began developing The Good Lord Bird in 2016.[4] For his work on the series, Hawke received nominations for the Golden Globe and Actor Award for Best Actor in a Miniseries or Television Film,[191][192] as well as a Writers Guild of America Award nomination for Television: Long Form – Adapted along his co-writers.[193]

Hawke collaborated again with Blum, Cargill, and Derrickson on the supernatural horror film The Black Phone (2021), portraying a masked serial killer of children.[194][195] Up to that point, Hawke had avoided playing villains for fear of being typecast by audiences.[195] However, he accepted the role because he was intrigued by the idea of wearing a mask for most of the film's runtime, comparing it to the masked performers of Ancient Greek theater.[194] Hawke said it allowed him to focus on physicality and voice acting, instead of facial expressions.[194] Empire praised him for a "frightening and fascinating physical performance" and a critic for the Roger Ebert website said that he effectively conveyed the character's "personality reversal" through his voice, body language, and eyes.[196][197] The Black Phone was commercially successful, grossing $161.4 million.[198] Released in February 2021, Hawke's third novel and fifth book, titled A Bright Ray of Darkness, drew direct inspiration from his real-life experiences.[199][200] Ron Charles described it as a "witty, wise and heartfelt novel about a spoiled young man growing up and becoming, haltingly, a better person".[201]

Hawke traveled to Ireland to film Robert Eggers's Viking epic The Northman (2022) as part of its ensemble cast.[202] Owen Gleiberman appreciated the quality of "squalid humanity" brought by Hawke in his portrayal of King Aurvandill and Justin Chang wished that he had been given more screen time.[203][204] He next starred in the comedy-drama film Raymond & Ray (2022), portraying along with Ewan McGregor two half-brothers.[205] The film received mixed reviews, but Hawke and McGregor's performances were praised;[206] a critic from the Roger Ebert website said that "only Hawke [had] the rough edges" that were needed for the film.[205] He played the antagonist Arthur Harrow in the superhero miniseries Moon Knight (2022), produced by Marvel Studios.[207] Although Hawke had previously criticized superhero films,[207] he accepted the role to create an original superpowered character and collaborate with co-star Oscar Isaac, who had initially offered him the part.[208] His portrayal of Harrow was inspired by psychiatrist Carl Jung and cult leader David Koresh.[194] Entertainment Weekly called him "unsettlingly charismatic" in the role,[209] while Variety said that Hawke and Isaac had managed to bring novelty to the Marvel Cinematic Universe.[210]

Hawke starred in the apocalyptic psychological thriller film Leave the World Behind (2023), portraying along with Julia Roberts a married couple living in Brooklyn.[211] James described the pair as "convincing" in their roles, adding that Hawke "easily [slid] into his character".[211] He then portrayed a gay gunslinger and sheriff in Pedro Almodóvar's Western melodrama short film Strange Way of Life (2023), which premiered at the 76th Cannes Film Festival.[212] Critics appreciated the chemistry between Hawke and co-star Pedro Pascal.[212][213][214] Meanwhile, he directed three biographical works: the six-part documentary The Last Movie Stars (2022) about actors Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward;[215] the film Wildcat (2023) about author Flannery O'Connor, starring Hawke's daughter Maya;[216] and the documentary film Highway 99: A Double Album (2025) about country singer Merle Haggard.[217] Wildcat premiered at the 50th Telluride Film Festival to mixed reviews.[216]

Hawke and Linklater's ninth film together was Blue Moon (2025),[218] a biopic in which Hawke starred as lyricist Lorenz Hart reflecting on himself on the opening night of the musical Oklahoma!.[219] Linklater had shared the draft with Hawke over a decade earlier,[218] but chose to delay the project until Hawke became old enough to portray a middle-aged Hart.[219] Hawke shaved his head and used stagecraft devices that made him appear shorter for the role, undergoing a transformation that he said helped him better understand the character's feelings.[219] The Houston Chronicle praised his performance as one of the year's best,[220] while NBC News described it as a career highlight.[221] It earned him nominations for the Academy Award, BAFTA, Golden Globe, and Actor Award for Best Actor.[222][223][224][225]

Later that year, Hawke reprised his role from The Black Phone in its sequel, Black Phone 2,[226] which grossed $132 million.[227] Frank Scheck said that Hawke "deliver[ed] one for the ages",[226] while The New York Times remarked that his performance "create[d] a more cohesive picture than the original".[228] He then portrayed an investigative journalist in the crime drama series The Lowdown (2025).[229] Critics identified the role as one in a series of Hawke's portrayals of self-righteous heroic characters driven to extremes that included his performances in First Reformed and The Good Lord Bird; The New Republic added that Hawke had been able to reiterate the archetype in a "striking variety of ways" across different genres.[230][229][231] He then starred in the historical film The Weight, which premiered at the 2026 Sundance Film Festival.[232]

Hawke is set to reprise his role from The Lowdown in its second season and star in a film of adaptation of journalist Monte Reel's 2010 book The Last of the Tribe.[233][234] He has stated that he and Linklater have been working on a period film.[235]

Acting style and reception

Hawke has been recognized for his versatility across a wide range of roles.[4][236][237] He enjoys the challenges posed by acting in different genres and settings with their own distinct rules,[238] but identifies himself primarily as a dramatic actor.[239] The Observer described his characters as "rarely [...] easily likable", but "flawed and complex".[240] The Globe and Mail called him one of the "hardest-working" contemporary character actors,[239] while scholar Gary Bettinson said that Hawke exemplifies what film historian Jeanine Basinger described as a "neo-star" – an actor who combines elements of a traditional film star and a character actor.[241]: 2 The A.V. Club described Hawke's career turn to genre films starting from the late 2000s as unexpected but successful, calling him the greatest contemporary "genre star".[242] Esquire named Hawke the greatest actor of his generation, praising his varied body of work as a departure from contemporary Hollywood conventions.[237] A critic for IndieWire remarked that each director Hawke has collaborated with has elicited a distinct aspect of his screen persona.[243]

Theater critic John Lahr opined that Hawke had first developed the skills that acting demands—"empathy, imagination, charm, [and] surrender"—through his experiences growing up with his mother.[4] Hawke said that his experience on the set of Before Sunrise allowed him to develop his own acting technique and style, instead of relying on imitating others.[4] His method involved "breaking the mask we wear for the world and letting as much truth seep out [...] as possible".[4] After increasing his stage work in the 2000s, Hawke said that theater helped him hone his craft and shaped him into his ideal version of an actor.[244] He enjoys theater because it grants actors control over their performance without the intervention of editing.[245] Hawke named theater director Austin Pendleton as the "only acting teacher [he's] ever had".[244]

Hawke later described acting as a "shamanistic process" in which one devotes themselves to the portrayal of a character, comparing it to a musician trying to understand the rhythm and sound of a song.[246] By the 2020s, Hawke had begun practising "third-person acting"[a] as opposed to the "first-person acting"[b] technique that he had favored early on in his career.[247] Bettinson described him as a "naturalistic" actor in the New Hollywood tradition and the Observer characterized his approach to acting as having a "conversational quality".[241]: 2 [240] Hawke memorizes scripts by rewriting them by hand "like it's [his] journal" and recording himself while reciting lines.[245]

Hawke said that he was greatly influenced by the New Hollywood movement.[241] He has cited Robert De Niro and Denzel Washington as major influences, admiring their work ethic and initiative on the set of his collaboration with De Niro on Great Expectations and with Washington on Training Day.[246] Hawke later referred to Washington as the "greatest actor of our generation".[249] Hawke has credited several directors as key influences including his collaborators Linklater and Peter Weir, who showed him "what filmmaking could be".[238]

Hawke and Linklater established a creative partnership that spanned four decades, making nine films together mainly focused on the theme of time.[236][238] Critic Justin Chang called the Before trilogy "Hawke's signature achievement" and his character, Jesse, the "quintessential Hawke character", described as a "charmingly outspoken know-it-all, ardently romantic, philosophical and a bit of a blowhard".[250] Chang opined that over the course of their collaboration Linklater managed to "tease out [Hawke's] sharpest dimensions as an actor and refuse[d] to treat him as just another pretty face".[250] Scholar Jennifer O'Meara argued that Linklater's collaborative filmmaking empowered Hawke to successfully branch out into writing and directing, remarking that critical praise for both the Before trilogy and Hawke's novels focused on character development.[251]

Hawke has received several lifetime achievement awards honoring his diverse career that encompasses film, television, theater, and literary work.[252][253][254] He found being labeled only as an actor early on in his career to be restricting, as he believes that art forms "are not as different as people make them out to be — that communication and storytelling and expression are all fundamentally coming from the same well".[246] O'Meara named him as an example of the "actor-writer" — a figure that challenges the traditional view of the director as the sole creative authority in film.[251] Chang called Hawke's career the "richest, most accomplished and surprising [...] of any actor now working in American movies".[250] Journalists have described his career as representative of Gen X's life trajectory, and attributed its longevity to his strategy of taking on diverse genres and roles.[c] GQ remarked that Hawke has managed to embody the main moments in a man's life—from high school in Dead Poets Society, through first love in Before Sunrise and fatherhood in Boyhood, and into middle age in First Reformed and Juliet, Naked—through his roles.[259]

"The idea of artistic integrity is a real balancing act. [...] Paul Schrader can want you but if he can't raise the money with you attached, you're going to lose that role."

Hawke has become known for eschewing to seek commercial success or fame as a film star, saying that he did not wish to become a "name brand".[236][240][260] He has starred in both independent cinema and Hollywood blockbusters, but called the former his "first love".[239][243] A critic for IndieWire said that "there's hardly anyone who can flit between arthouse stuff and big-money studio schlock [...] as effortlessly as he".[243] Hawke has commented on the need to balance less profitable independent productions with commercial films to support his family and several charities.[261] Although Hawke has expressed disinterest for being in the public sphere, he frequently participates in press tours to promote his films, saying that "if you want people to have a chance to see a movie [...] you have to do it".[238][244] Throughout his career, interviewers have described him as having a energetic, chatty, and "boyish" personality.[d] The New Yorker remarked that Hawke's later public persona has become that of a "rough-edged, raucous actor" with a "full-blown [and] happy maturity".[4]

Personal life

On May 1, 1998, Hawke married actress Uma Thurman, whom he had met on the set of Gattaca in 1996.[264][265] They have two children, Maya (born 1998) and Levon (born 2002), both of whom became actors.[266] The couple separated in 2003 amidst allegations of infidelity and filed for divorce the following year, which was finalized in August 2005.[267][268][269] Hawke and Thurman were described as a supercouple, with their marriage and divorce becoming the subject of intense tabloid scrutiny, much to their displeasure.[270][271] Hawke found the tabloid attention "humiliating even when they [were] saying positive things".[236] In June 2008, Hawke married Ryan Shawhughes, a Columbia University graduate who had previously worked briefly as a nanny for his children with Thurman.[272][273] He stated that their relationship had begun a year after his divorce and that his first marriage had ended for reasons unrelated to Shawhughes.[273] Together, they have two daughters and run a production company called Under the Influence Productions.[266][274]

An Episcopalian, Hawke has said that faith played a larger role in his youth but that he failed to develop it further in adulthood.[216] He is an advocate for gay rights, releasing a video with Shawhughes supporting same-sex marriage in New York in 2011.[275] He identifies as a feminist and has criticized the film industry for being "such a boys' club".[276][277] A staunch supporter of the Democratic Party, Hawke has endorsed presidential candidates Bill Bradley in 2000,[278] Barack Obama in 2008,[279] Hillary Clinton in 2016,[280] and Kamala Harris in 2024.[281] He criticized Donald Trump, the 45th and 47th president of the United States, for his Make America Great Again slogan and for threatening to put Clinton in jail.[282] In 2015, Hawke advocated for the protection of St. Georges Bay, Canada, against oil and gas explorations, participating in an event organized by the local Mi'kmaq community and saying that the wishes of First Nations people should be respected; he had owned property in the area since 2000.[283]

Hawke began participating in charity work at the behest of his mother,[284] who encouraged him to donate a portion of his salary from Dead Poets Society to the Doe Fund, a non-profit.[284] He attended their annual fundraising gala in October 2011 and ran the New York City Marathon alongside Shawhughes in November 2015 in support of the non-profit.[285][286] Hawke serves on the board of trustees of his mother's foundation, the Alex Fund.[287] He served as co-chair of the Young Lions Committee, one of the New York Public Library's (NYPL) major philanthropic boards, and co-founded the Young Lions Fiction Award in 2001.[288][289] He was named a Library Lion by the NYPL in November 2010 and joined the library's board of trustees in May 2016.[290][291] He joined the board of trustees of the Classical Theatre of Harlem in April 2023 and made fundraising videos for the American Library Association and the Coolidge Corner Theatre.[292][293][294]

Publications

- Hawke, Ethan (1996). The Hottest State: A Novel (1st ed.). Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-54083-4. OCLC 34474927 – via Internet Archive.

- Hawke, Ethan (2002). Ash Wednesday: A Novel (1st ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-41326-1. OCLC 48967928 – via Internet Archive.

- Hawke, Ethan (April 2009). "The Last Outlaw Poet". Rolling Stone. No. 1076. pp. 50–61, 78–79. ISSN 0035-791X. Archived from the original on April 10, 2009.

- Hawke, Ethan (2015). Rules for a Knight (1st ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0307962331 – via Internet Archive.

- Hawke, Ethan (2016). Indeh: A Story of the Apache Wars (1st ed.). New York: Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-1-401-31099-8 – via Internet Archive.

- Hawke, Ethan (2021). A Bright Ray of Darkness: A Novel (1st ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-1-785-15260-3. OCLC 34474927 – via Google Books.

Notes

- ^ Hawke defined "third-person acting" as a technique, similar to character acting, in which the actor aims to disappear into the role and become unrecognizable across different portrayals. He named Daniel Day-Lewis and Philip Seymour Hoffman as examples of "third-person actors".[247][248]

- ^ Hawke defined "first-person acting" as a technique in which the actor's public persona informs every portrayal, ensuring that they remain recognizable to audiences across different roles. He named Paul Newman as an example of a "first-person actor".[247]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[236][255][256][257][258]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[238][262][263][246]

References

- ^ Morales, Tatiana (July 1, 2004). "Ethan Hawke's Love Before Sunset". CBS News. Archived from the original on January 2, 2026. Retrieved December 11, 2025.

- ^ a b Schindehette, Susan (June 17, 2002). "Mom on a Mission". People. Archived from the original on November 7, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ Solomon, Deborah (September 16, 2007). "Renaissance Man?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 11, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lahr, John (September 11, 2020). "The Many Faces of Ethan Hawke". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ Grossman, Anna Jane (January 20, 2012). "Vows: Leslie Hawke and David Weiss". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 2, 2014. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ "Ethan Hawke". Inside the Actors Studio. Season 8. Episode 12. April 21, 2002. Bravo.

- ^ a b c Myers, Marc (October 6, 2020). "Ethan Hawke Was Shaped by His Mom's Independence". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 27, 2022. Retrieved October 18, 2025.

- ^ Phillipp, Charlotte (July 26, 2024). "Former Jeopardy Winner Working as Teacher at N.Y.C. Private School Accused of Soliciting Child Sex Abuse Images". People. Archived from the original on August 6, 2024. Retrieved October 18, 2025.

- ^ Higgins, Bill (November 27, 2014). "Throwback Thursday: In 1985, Ethan Hawke Began His Own Film Boyhood". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 5, 2024. Retrieved October 18, 2025.

- ^ Complex, Valerie (June 7, 2024). "Ethan Levy Signs with Ann Steele Agency". Deadline. Archived from the original on June 7, 2024. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ Hurlburt, Roger (June 25, 1989). "Earning His Wings". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. p. 3F.

- ^ "The Ultimate New Jersey High School Yearbook — A-K". The Star-Ledger. June 7, 1998. p. 1.

- ^ Preston, Alex (January 30, 2021). "Ethan Hawke: 'It's Just a Petrifying Time to Speak About Male Sexuality'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 23, 2024. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ a b Brockes, Emma (December 8, 2000). "Ethan Hawke: I Never Wanted to Be a Movie Star". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 2, 2024. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ a b Vadeboncoeur, Joan (January 22, 1995). "Despite Film Success, Hawke Keeps A Keen Eye on Theater". Syracuse Herald American. p. 17.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Dana (April 14, 2002). "The Payoff for Ethan Hawke". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 5, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (July 12, 1985). "The Screen: Explorer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 13, 2025. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Halpern, Dan (October 7, 2005). "Interview: Dan Halpern Meets Ethan Hawke". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 28, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ "Explorers". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on October 20, 2025. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ "Dead Poets Society". Variety. January 1, 1989. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ Barlow, Helen (June 20, 2008). "Entertainment News". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on December 9, 2025. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^

- "Dead Poets Society". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- "Dead Poets Society". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on February 11, 2023. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- "Dead Poets Society (1989) – Box Office and Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- Buckmaster, Luke (July 16, 2019). "Dead Poets Society: 30 years on Robin Williams' Stirring Call to 'Seize the Day' Endures". The Guardian. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ "Ethan Hawke • Interview (Dad)". March 6, 2024 [1989]. Archived from the original on December 23, 2025. Retrieved October 19, 2025 – via YouTube.

- ^ Hawke, Ethan (September 27, 2016). "Ethan Hawke: Why I Chose New York Over Los Angeles". Variety. Archived from the original on December 25, 2025. Retrieved December 11, 2025.

- ^ Landman, Beth; Spiegelman, Ian (April 11, 2019). "May 15, 2000". New York. Archived from the original on August 14, 2007. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ Brodesser-Akner, Taffy (August 28, 2018). "Ethan Hawke Is Still Taking Ethan Hawke Extremely Seriously". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 31, 2025. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ Abele, Robert (January 21, 2018). "White Fang Film Review: Jack London Classic Gets Sturdy, Simplistic Animated Retelling". TheWrap. Archived from the original on January 7, 2026. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ Wilmington, Michael (January 18, 1991). "Movie Review: White Fang Gentles the Jack London Saga". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 4, 2023. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ Mahar, Ted (January 24, 1991). "White Fang: A Boy, A Mine and a Dog". The Oregonian. p. C14.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 18, 1991). "White Fang Movie Review & Film Summary (1991)". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on October 14, 2025. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ Flint, Hanna (January 18, 2021). "The Timeless Appeal of One-Man-and-His-Dog Stories". BBC Culture. Archived from the original on August 18, 2025. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ "A Midnight Clear". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on August 26, 2025. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ Rich, Frank (November 30, 1992). "Review/Theater: The Seagull; A Vain Little World of Art and Artists, Painted by Chekhov". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 15, 1993). "Alive Review". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on January 18, 2014. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (February 18, 1994). "Reality Bites Movie Review & Film Summary (1994)". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ James, Caryn (February 18, 1994). "Review/Film; Coming of Age in Snippets: Life as a Twentysomething". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ "Reality Is a Gen-X Film with Satirical Bite". Orlando Sentinel. October 17, 1999. Archived from the original on April 4, 2016. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ Rickey, Carrie (April 3, 1994). "Generation X Turns Its Back". The Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ^ Hoad, Phil (November 4, 2019). "Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke: How We Made the Before Sunrise Trilogy". The Guardian. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (January 27, 1995). "An Extraordinary Day Dawns Before Sunrise". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 19, 2008. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ "Before Sunrise". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on February 23, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ Breihan, Tom (March 7, 2022). "The Number Ones: Lisa Loeb & Nine Stories' 'Stay (I Missed You)'". Stereogum. Archived from the original on December 24, 2025. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ "The Best Ethan Hawke Scene". The Guardian. December 19, 2000. Archived from the original on May 9, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- ^ Levy, Joe (December 1994). "A Dress for Success: Lisa Loeb, 'Stay'". Video of the Year. Spin. Vol. 10, no. 9. p. 90. ISSN 0886-3032. Archived from the original on October 9, 2023. Retrieved September 23, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ Lazare, Lewis (October 9, 1995). "Buried Child". Variety. Archived from the original on December 25, 2025. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (October 18, 1996). "The Hottest State — Book Review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 25, 2009. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ Nessel, Jen (November 3, 1996). "Love Hurts". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- ^ Chanko, Kenneth M. (October 26, 1997). "Hawke-ing the Future in Science-Fiction Thriller Gattaca". U-T San Diego. p. E-6.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (October 24, 1997). "Gattaca Movie Review & Film Summary (1997)". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on August 7, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ Travers, Peter (January 30, 1998). "Great Expectations". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 17, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ "Ethan Hawke Goes Back in Time to Visit His Most Iconic Characters". GQ. August 6, 2018. Archived from the original on September 4, 2025. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ Stack, Peter (March 27, 1998). "Bank-Robbing 'Newton' Brothers Show Boys Will Be Boys". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 30, 2009. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ "The Newton Boys". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on December 25, 2025. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ Brantley, Ben (June 28, 1999). "Theater Review; Lost Souls, Not so Different from Their Creator". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (May 12, 2000). "Snow Falling On Cedars". The Guardian. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ "Snow Falling on Cedars". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (January 7, 2000). "Snow Falling on Cedars — Movie Review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 22, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Dominguez, Robert (May 11, 2000). "A Renaissance Man Tackles Shakespeare Hamlet's Ethan Hawke Has More on His Mind Than Movie Stardom". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on December 25, 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ "Waking Life Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ "Tape Reviews". Metacritic. November 2, 2001. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (October 12, 2001). "Surreal Adventures Somewhere Near the Land of Nod". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 7, 2010. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ Denby, David (November 12, 2001). "Tape". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 7, 2008. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- ^ Ayer, David (September 9, 2001). "A Story From the Streets". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 28, 2025. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (October 5, 2001). "Washington's Arresting Performance Drives a Thrilling Training Day". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 27, 2025. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ "Training Day Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 11, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ Clinton, Paul (October 4, 2001). "Review: Training Day a Course Worth Taking". CNN. Archived from the original on May 11, 2009. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ "SAG Awards Nominations in Full". BBC News. January 29, 2002. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Brook, Tom (March 21, 2002). "Ethan Hawke's Oscar Surprise". BBC News. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Diones, Bruce (May 6, 2002). "The Film File: Chelsea Walls". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ "Best Sellers; Hardcover Fiction". The New York Times Book Review. August 11, 2002. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ Falconer, Helen (October 19, 2002). "Review: Ash Wednesday by Ethan Hawke". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 17, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ James, Caryn (August 16, 2002). "Books of the Times; So He's Famous. Give Him a Break, If Not a Free Ride". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ Simon, John (November 24, 2003). "Star Turns". New York. Archived from the original on May 11, 2009. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ Brantley, Ben (November 21, 2003). "Theater Review; Falstaff and Hal, With War Afoot". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ "Taking Lives (2004): Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on April 24, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ Covert, Colin (March 19, 2004). "Lives Digs Its Own Grave". Star Tribune. p. 12E.

- ^ Pulver, Andrew (October 3, 2019). "Julie Delpy 'refused' to Be in Before Midnight Without Rqual Pay". The Guardian. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ Denby, David (May 20, 2013). "Couples". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 19, 2025. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ Wilmington, Michael (July 1, 2004). "Movie Review: Before Sunset". The Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved September 2, 2009.

- ^ Adler, Shawn (July 5, 2007). "Ethan Hawke Laments Lost before Sunset Threequel". MTV News. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ^ Marshall, Lee (July 19, 2004). "Love That Goes with the Flow". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ^ Leopold, Todd (January 25, 2005). "Aviator Leads Oscar Nominations". CNN. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ^ Davis, Sandi (January 19, 2005). "Violence Dominates Story Line Behind Precinct 13". The Oklahoman. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ Clinton, Paul (January 20, 2005). "Review: An Enjoyable Assault on Precinct 13". CNN. Archived from the original on June 19, 2006. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13 Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on December 28, 2025. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on December 10, 2025. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ Bernard, Jami (January 19, 2005). "In Assault, a Reshoot Hits the Action Target". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on December 26, 2025. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ Mondello, Bob (August 24, 2007). "Ethan Hawke's Hottest State Is No Vanity Project". NPR. Archived from the original on September 20, 2025. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ "The Hottest State". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ McCarter, Jeremy (May 28, 2007). "Arise, Ye Prisoners of Tom Stoppard". New York. Archived from the original on October 13, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ Glitz, Michael (August 19, 2007). "'State' of Mind". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ "'I am not optimistic at all about American society': Sidney Lumet on Before the Devil Knows You're Dead". British Film Institute. June 21, 2024. Archived from the original on December 28, 2025. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ Oganesyan, Natalie (October 19, 2025). "Ethan Hawke Details How Sidney Lumet Pitted Him And Philip Seymour Hoffman Against Each Other For Before The Devil Knows You're Dead". Deadline. Archived from the original on October 20, 2025. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ "Before the Devil Knows You're Dead". The Guardian. July 21, 2008. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ "Before the Devil Knows You're Dead". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on October 29, 2025. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (November 1, 2007). "Before the Devil Knows You're Dead Is Darkly Real". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 2, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Travers, Peter (October 18, 2007). "Before the Devil Knows You're Dead". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 12, 2011. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ a b McCarter, Jeremy (November 16, 2007). "We've Seen the Lights Go out on Broadway". New York. Archived from the original on May 11, 2009. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ a b Dargis, Manohla (December 12, 2008). "Dead Ends in South Boston: Ethan Hawke and Mark Ruffalo in Crime Drama". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 13, 2023. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ Brunette, Peter (September 9, 2008). "What Doesn't Kill You". The Hollywood Reporter. The Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 30, 2025. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ "Labeouf, Bloom, Christie in 'Love You". Entertainment Weekly. April 10, 2008. Archived from the original on April 21, 2009. Retrieved May 1, 2009.

- ^ Webster, Andy (November 20, 2009). "Movie Reviews – Staten Island". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ Moore, Roger (January 4, 2010). "Ethan Hawke Dons Fangs for Daybreakers". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on January 9, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ Villarreal, Yvonne (January 8, 2010). "Ethan Hawke Says Daybreakers Aspires to Be Aliens with Fangs". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 5, 2025. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ Siegel, Tatiana (May 9, 2007). "Hawke bites on Lionsgate Daybreakers". The Hollywood Reporter. Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 24, 2025. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ "Daybreakers Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on November 15, 2024. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ "Daybreakers". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on November 1, 2025. Retrieved October 20, 2025.

- ^ a b Neumaier, Joe (March 5, 2010). "Brooklyn's Finest Star Ethan Hawke Perfectly Conveys Constant Threat of Job with New York Police". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ "Brooklyn's Finest Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on August 13, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Sternbergh, Adam (January 31, 2010). "The Ethan Hawke Actors Studio". New York. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 3, 2010. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Healy, Patrick (January 27, 2010). "New Search for the Truth in A Lie". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 25, 2010. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ^ Jacobson, Murrey (February 24, 2010). "Conversation: Ethan Hawke on Directing Shepard's A Lie of the Mind". PBS NewsHour. Archived from the original on February 26, 2010. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ^ Brantley, Ben (February 19, 2010). "Home Is Where the Soul Aches". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 25, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ^ Labrecque, Jeff (February 18, 2010). "Stage Review — A Lie of the Mind (2010)". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on March 17, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ^ Healy, Patrick (April 1, 2010). "Lucille Lortel Nominees Announced". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 4, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2010.

- ^ Cox, Gordon (May 3, 2010). "Drama Desk Fetes Ragtime, Scottsboro". Variety. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ "Moby Dick Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on December 3, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ Preston, John (June 10, 2010). "Ethan Hawke Interview". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ DeFore, John (September 13, 2011). "The Woman in the Fifth: Toronto Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 3, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ Ryan, Mike (October 9, 2012). "Ethan Hawke: It's 'Profoundly Disappointing' Ryan Is First Gen-X Candidate". HuffPost. Archived from the original on July 29, 2023. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Pols, Mary (October 11, 2012). "Just How Scary Is Sinister?". Time. Archived from the original on January 13, 2026. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ "Before Midnight, Love Darkens and Deepens". NPR. May 30, 2013. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Scott, A.O. (May 23, 2013). "Before Midnight, with Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 21, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ "Before Midnight Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on October 10, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Chang, Justin (January 21, 2013). "Review: Before Midnight". Variety. Archived from the original on January 19, 2014. Retrieved January 23, 2014.

- ^ Ford, Rebecca (January 16, 2014). "Oscars: 9 Films Nominated for Best Picture". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 17, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Young, Neil (May 31, 2013). "The Purge: Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 30, 2023. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ McClendon, Blair (October 27, 2020). "The Purge Films Reveal the Ugly Truth About America". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 19, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ "The Purge Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on October 26, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Labrecque, Jeff (June 10, 2013). "Ethan Hawke in The Purge and Before Midnight". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 25, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Healy, Patrick (May 22, 2012). "Ethan Hawke Will Star in and Direct New Play for New Group". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ^ Wang, K.S. (September 6, 2013). "Celebrity Drive: Ethan Hawke, Star of Getaway". Motor Trend. Archived from the original on December 30, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ "Getaway". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Rooney, David (November 21, 2013). "Macbeth: Theater Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Schager, Nick (July 10, 2014). "Time of Our Life: On Boyhood, a Coming-of-Age Epic About Simply Growing Up". Complex. Archived from the original on December 24, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ "The Best and Worst Movies of 2014". Metacritic. January 6, 2015. Archived from the original on March 12, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ "Best of 2014: Film Awards & Nominations Scorecard". Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 8, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ Hughes, Jason (December 3, 2014). "Ethan Hawke Didn't Expect Boyhood to Win Awards or Be Critically Acclaimed (Video)". TheWrap. Archived from the original on December 8, 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Buchanan, Kyle (January 15, 2015). "Ethan Hawke Is Helping His Boyhood Kids Through Oscar Season". Vulture. Archived from the original on September 26, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ "Oscars 2015: Best Supporting Actor". BBC News. January 15, 2015. Archived from the original on January 22, 2022. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Lewis, Hilary (January 11, 2015). "Golden Globes: Boyhood Wins Best Motion Picture, Drama". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 28, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ "Predestination". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on September 17, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Romney, Jonathan (February 22, 2015). "Predestination Review – the Ultimate Man-Walks-Into-a-Bar Anecdote". The Guardian. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Edelstein, David (January 9, 2015). "If You Love Time-Travel Movies, You'll Love the Ethan Hawke–Starring Predestination". Vulture. Archived from the original on December 28, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Rooney, David (September 5, 2014). "Good Kill: Venice Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 15, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Punter, Jennie (September 14, 2014). "Toronto: Imitation Game Wins Festival's People's Choice Award". Variety. Archived from the original on January 1, 2026. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (October 3, 2023). "Ethan Hawke & Maya Hawke Cover Willie Nelson's 'We Don't Run' For Light in the Attic Compilation". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 14, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Ho, Solarina (September 12, 2014). "Ethan Hawke Seymour Documentary Is Intimate Portrait of Pianist". Reuters. Archived from the original on September 24, 2016. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "Born to Be Blue (2015)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ "Maggie's Plan (2016)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Queenan, Joe (July 20, 2016). "Born to Be Blue: Ethan Hawke on the Fast Life and Mysterious Death of Chet Baker". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 5, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ^ Godfrey, Alex (November 29, 2014). "Ethan Hawke: 'Mining Your Life Is the Only Way to Stumble on Anything Real'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 4, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ Roeper, Richard (May 26, 2016). "Maggie's Plan: As Smart and Funny as Vintage Woody Allen". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Genzlinger, Neil (August 13, 2015). "Review: Ten Thousand Saints, a Coming of Age in the East Village, Circa 1980s". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 30, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Abele, Robert (February 5, 2016). "Review: Emma Watson and Ethan Hawke Are Misused in Questionable Hypnosis Tale Regression". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 28, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Lach, Eric (November 9, 2015). "Ethan Hawke Explains His Thing for Knights". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on June 10, 2017. Retrieved July 8, 2017.

- ^ Barker, Andrew (March 12, 2016). "SXSW Film Review: In a Valley of Violence". Variety. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ DeFore, John (March 12, 2016). "In a Valley of Violence: SXSW Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ Scheck, Frank (June 22, 2016). "The Phenom: Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 13, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Smith, Nigel M. (April 18, 2016). "The Phenom Review: Baseball Movie Throws a Curveball". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 19, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Roeper, Richard (June 22, 2017). "Maudie: Sally Hawkins Delights as a Hard-Luck Pauper Who Loves Life". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on July 4, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (June 15, 2017). "Maudie Review: Sally Hawkins Saves an Otherwise Missed Opportunity". TheWrap. Archived from the original on July 11, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Hertz, Barry (September 6, 2016). "How Ethan Hawke Survived Hollywood". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on September 7, 2016. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Lee, Ashley (July 18, 2016). "Magnificent Seven Trailer: Chris Pratt, Denzel Washington Introduce the Reboot's Misfits". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 19, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Hicks, Tony (September 20, 2016). "Review: Magnificent Seven Hits Its Target". East Bay Times. Archived from the original on December 24, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (September 25, 2016). "Weekend Box Office: Magnificent Seven Gallops to No. 1 with $35M". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 28, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ "Invasion!". Tribeca Festival. Archived from the original on December 29, 2025. Retrieved November 10, 2025.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (April 29, 2017). "Amazon & Netflix Lead Daytime Creative Arts Emmy Awards Winners- Full List". Deadline. Archived from the original on April 30, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2025.

- ^ Nance, Kevin (May 19, 2016). "Ethan Hawke on Indeh and the Pull of Apache Stories". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 24, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Collins, K. Austin (May 18, 2018). "Review: In the Masterful First Reformed, Ethan Hawke Gives Us a God-Fearing Travis Bickle". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on October 4, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Chang, Justin (May 17, 2018). "Review: The Bracing First Reformed, Starring a Superb Ethan Hawke, Resurrects Paul Schrader's Career". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 13, 2023. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Collins, K. Austin (January 3, 2019). "First Reformed Was the Role Ethan Hawke's Entire Career Has Been Leading Up To". Slate. Archived from the original on January 10, 2026. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Lee, Benjamin (January 18, 2018). "Sundance 2018: #MeToo Movement Set to Colour First Post-Weinstein Festival". The Guardian. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ "Blaze: Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. January 21, 2018. Archived from the original on April 25, 2023. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (January 20, 2018). "Film Review: Juliet, Naked". Variety. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Fleishman, Jeffrey (June 8, 2017). "Ethan Hawke Lets Us in His Editing Room and Reveals What Philip Seymour Hoffman Taught Him". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ "True West Paul Dano and Ethan Hawke Star in Sam Shepard's Pulitzer-Nominated Drama". Broadway.com. 2018. Archived from the original on December 23, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ Hoefler, Robert (January 24, 2019). "True West Broadway Review: Ethan Hawke Soars, Paul Dano Flits in Sam Shepard Drama". TheWrap. Archived from the original on December 19, 2025. Retrieved December 15, 2025.

- ^ Soloski, Alexis (January 25, 2019). "True West Review – Ethan Hawke and Paul Dano Go South in Mediocre Drama". The Guardian. Retrieved December 15, 2025.

- ^ Stasio, Marilyn. "Broadway Review: True West with Ethan Hawke, Paul Dano". Variety. Archived from the original on December 19, 2025. Retrieved December 15, 2025.

- ^ Hipes, Patrick (February 21, 2019). "The Kid Trailer: Ethan Hawke Vs. Dane DeHaan in Vincent D'Onofrio's Wild West Tale". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2025.

- ^ Ebiri, Bilge (March 8, 2019). "The Kid Is an Old West Adventure Refashioned As a Grotesque Nightmare". Vulture. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ "Adopt a Highway". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on March 7, 2022. Retrieved December 14, 2025.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (December 15, 2025). "Venice Film Festival to Open with Hirokazu Kore-eda's The Truth". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on December 19, 2025. Retrieved December 15, 2025.

- ^ Sollosi, Mary. "Catherine Deneuve Is As Magnifique As Ever in The Truth: Review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 7, 2025. Retrieved December 14, 2025.

- ^ Duralde, Alonso (August 28, 2019). "The Truth Film Review: Catherine Deneuve and Juliette Binoche Grapple with Honesty and Each Other". TheWrap. Archived from the original on December 28, 2025. Retrieved December 14, 2025.

- ^ a b Davids, Brian (August 18, 2020). "'What Would David Bowie Do?': How Ethan Hawke and Michael Almereyda Shed Light on Nikola Tesla". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Nicholson, Amy (January 28, 2020). "Tesla: Film Review". Variety. Archived from the original on April 23, 2024. Retrieved December 14, 2025.

- ^ Roeper, Richard. "Tesla: Jolts of Creative Whimsy Electrify a Delightfully Oddball Biopic". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on January 4, 2026. Retrieved December 14, 2025.

- ^ Lang, Brent (June 12, 2018). "Ethan Hawke, Jason Blum Adapting The Good Lord Bird for TV (Exclusive)". Variety. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved December 15, 2025.

- ^ Mauch, Ally; Rice, Nicholas (February 28, 2021). "Two of Mark Ruffalo's Three Kids Make a Virtual Appearance as He Accepts His Golden Globe Win". People. Archived from the original on April 1, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ "The 27th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards". Screen Actors Guild. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2022.