| Real Name | Maximillian George Carnarius |

|---|---|

| Net Worth 2026 | $36 million USD |

| Birthday (Year-Month-Day) | 1890-1-11 |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | professional baseball player |

| Height | 1.8 m or 5 ft 11 inches |

| Weight | 77 kg or 170 pounds |

| Marital Status | Married (Aurelia Behrens) |

| Ethnicity | American |

| Education | Concordia College |

| Kids | 2 |

| Kids Names |

| Max Carey | |

|---|---|

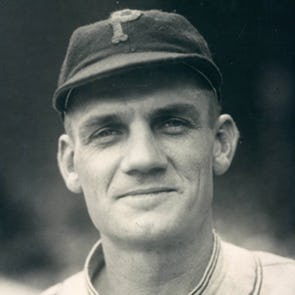

Carey in 1921 | |

| Outfielder / Manager | |

| Born: January 11, 1890 Terre Haute, Indiana, U.S. | |

| Died: May 30, 1976 (aged 86) Miami, Florida, U.S. | |

Batted: Switch Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| October 3, 1910, for the Pittsburgh Pirates | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| September 29, 1929, for the Brooklyn Robins | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .285 |

| Hits | 2,665 |

| Home runs | 70 |

| Runs batted in | 802 |

| Stolen bases | 738 |

| Managerial record | 146–161 |

| Winning % | .476 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Managerial record at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1961 |

| Election method | Veterans Committee |

Maximillian George Carnarius (January 11, 1890 – May 30, 1976), also known as Max George Carey, was an American professional baseball center fielder and manager. Carey played in Major League Baseball for the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1910 through 1926 and for the Brooklyn Robins from 1926 through 1929. He managed the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1932 and 1933.

Carey starred for the Pirates, helping them win the 1925 World Series. During his 20-year career, he led the league in stolen bases ten times and finished with 738 steals, a National League record until 1974 and still the 9th-highest total in major league history. Carey was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1961.

Early life

Maximillian George Carnarius was born in Terre Haute, Indiana, on January 11, 1890. His father was a Prussian soldier and swimming teacher. He had emigrated to the United States after the Franco-Prussian War and worked as a contractor.[1]

Carey's parents wanted their son to become a Lutheran minister. He attended Concordia College in Fort Wayne, Indiana, studying in the pre-ministerial program. He also played baseball, and was a member of the swimming and track-and-field teams. After graduating in 1909, he went to Concordia Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri.[1]

Professional career

Minor league baseball

In the summer of 1909, Carey attended a game of minor league baseball's Central League between the Terre Haute Hottentots and the South Bend Greens. South Bend was without a starting shortstop, as they had sold theirs to another team. Carey found Aggie Grant, South Bend's manager, and convinced Grant to give him the opportunity to fill in for the remainder of the season, based on his track-and-field skills. He used the name "Max Carey" in order to retain his amateur status at Concordia College. He had a .158 batting average and committed 24 errors in 48 games.[1][2]

Carey returned to play for South Bend in the 1910 season. The team had a new shortstop, Alex McCarthy, so Carey agreed to play as their left fielder. He had a .298 batting average with 86 stolen bases in 96 games. He also recorded 25 assists. Able to make a career in baseball, Carey decided to drop out of Concordia.[1]

Major League Baseball

The president of the Central League recommended Carey to the Pittsburgh Pirates of Major League Baseball's (MLB) National League towards the end of the 1910 season. The Pirates bought Carey and McCarthy from South Bend on August 15. Carey made his MLB debut with the Pirates, appearing in two games as a replacement for Fred Clarke during the 1910 season.[1][3]

In 1911, Carey played in 122 games as the Pirates' center fielder, replacing Tommy Leach.[4] He had a .258 batting average on the season.[5] The next year, he succeeded Clarke as the Pirates' left fielder on a permanent basis.[4] In 1913, Carey led the National League in plate appearances (692), at bats (620), runs scored (99), and stolen bases (61).[6] In 1914, he led the National League in games played (156), at bats (596), and triples (17).[7] He led the National League in steals in 1915 (36),[8] 1916 (63),[9] 1917 (46),[10] and 1918 (58), while also leading the league with 62 walks in 1918.[11] After the 1915 season, Carey went on a barnstorming tour with Dave Bancroft.[12]

Carey missed much of the 1919 season with an injury, but returned to form in the 1920 season.[1] He again led the National League in steals in 1920, with 52,[13] in the 1922 season with 51,[14] in the 1923 season with 51,[15] in the 1924 season with 49,[16] and in the 1925 season with 46.[17] In the 1922 season, he was only caught stealing twice.[4]

In 1924, Carey altered his batting stance based on Ty Cobb's. He had a .343 batting average in the 1925 season, and the Pirates won the National League pennant that year. In the deciding game of the 1925 World Series, Carey had four hits, including three doubles, off of Walter Johnson.[1] Carey's .458 batting average led all players in the series, and the Pirates defeated the American League's Washington Senators.[18] He hit for a batting average over .300 three seasons in a row from 1921 to 1923. He led the league in stolen bases eight times, including each season between 1922 and 1924.[2] He regularly stole 40 or more bases and maintained a favorable steal percentage; in 1922 he stole 51 bases and was caught only twice. He also stole home 33 times in his career, second best only to Ty Cobb's 50 on the all-time list.

In 1926, Clarke, now the team vice president, was also serving as an assistant to manager Bill McKechnie. Clarke would sit on the bench in full uniform and give advice to McKechnie. Carey ended up in a slump that summer and one day Clarke commented to McKechnie that they should replace Carey, even if they had to replace him with a pitcher. When Carey found out about the remark, he called a team meeting, along with Babe Adams and Carson Bigbee, who were also discontented with Clarke. The players voted on whether Clarke should remain on the bench during games. The players voted 18–6 in favor of Clarke remaining on the bench. Clarke found out about the meeting and ordered that the responsible players were to be disciplined.[19] Adams and Bigbee were released, while Carey was suspended.[20] The Pirates placed Carey on waivers and he was claimed by the Brooklyn Robins.[19] Carey played his final three and a half years with the Robins, but he was aging and no longer the same player. Carey retired in 1929.

Later career

Carey returned to the Pirates as a coach for the 1930 season.[21] After sitting out the 1931 season, he became the manager of the Dodgers before the 1932 season, succeeding Wilbert Robinson.[22][23] He traded for outfielder Hack Wilson,[24] and traded Babe Herman, also an outfielder, for third baseman Joe Stripp.[25] Behind Wilson, Brooklyn finished in third place in the National League in 1932. However, the team struggled in the 1933 season, leading to outrage when the club renewed his contract for 1934 in August.[26] Receiving criticism by Brooklyn newspapers, he was replaced before the 1934 season by Casey Stengel, and remarked that he became "the first manager fired by the newspapers".[1] The organization stated that they fired Carey due to his inability to get along with his players.[27]

Carey worked as a scout for the Baltimore Orioles and served as a minor league manager.[28] He was the manager and general manager of the Miami Wahoos of the Florida East Coast League in 1940 and 1941.[1] In 1944, Carey became the manager of the Milwaukee Chicks in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL). That year, Milwaukee won the AAGPBL pennant.[1] Beginning in 1945, he spent several years as the league's president.[29] He then spent three seasons managing the league's Fort Wayne Daisies.[28]

Later life

Carey moved to Florida, and became involved in real estate. Carey lost more than $100,000 ($1,875,000 in current dollar terms) in the 1929 stock market crash. He became a writer in the 1950s. He self-published a book on baseball strategy and authored magazine articles for publications such as Esquire.[1] He also served on the Florida State Racing Commission.[30]

In 1961, the Veterans Committee elected Carey and Billy Hamilton to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.[31]

In 1968, Carey joined other athletes in supporting Richard Nixon's presidential campaign. The athletes created a committee called Athletes for Nixon.[32]

Carey died on May 30, 1976, at age 86 in Miami, Florida. He was buried in Woodlawn Park Cemetery and Mausoleum (now Caballero Rivero Woodlawn North Park Cemetery and Mausoleum). He was survived by his wife, Aurelia, and a son, Max Jr.[30]

Legacy

Carey was nicknamed "Scoop" for his ability to catch fly balls in front of him.[33] His mark of 738 stolen bases remained a National League record, until Lou Brock surpassed it in 1974.[34]

When Carey was young, his mother sewed special pads into his uniform to protect his legs and hips while sliding. Carey went on to patent these sliding pads.[1][35][36] He also shared a patent on a liniment called Minute-Rub.[1]

See also

- Major League Baseball titles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball stolen base records

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career stolen bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual stolen base leaders

- List of Major League Baseball players to hit for the cycle

- List of Major League Baseball single-game hits leaders

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Bennett, John. "The Baseball Biography Project – Max Carey". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved June 10, 2007.

- ^ a b Waldo, Ronald (2011). The Battling Bucs of 1925: How the Pittsburgh Pirates Pulled Off the Greatest Comeback in World Series History. McFarland. p. 25. ISBN 978-0786487899. Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- ^ "1910 Pittsburgh Pirates". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Carey's Path to the Hall of Fame". The Miami News. January 30, 1961. Retrieved October 29, 2017 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "1911 Pittsburgh Pirates". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ "1913 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ "1914 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ "1915 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ "1916 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ "1917 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ "1918 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ "The Gazette Times". Retrieved November 4, 2014 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ "1920 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ "1922 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ "1923 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ "1924 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ "1925 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ "1925 World Series - Pittsburgh Pirates over Washington Senators (4-3) - Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Waldo, Ronald (2010). Fred Clarke: A Biography of the Baseball Hall of Fame Player-Manager. McFarland. pp. 203–205. ISBN 978-0786460168. Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- ^ "Pirates Drop Vets, Suspend Their Captain". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved November 7, 2014 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ Boyle, Havey J. (October 31, 1930). "Mirrors of Sport". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved November 4, 2014 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ "Carey Gets Pilot's Job Of Dodgers". Schenectady Gazette. AP. October 24, 1931. Retrieved November 7, 2014 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ Talbot, Gayle (January 5, 1932). "Max Carey Says He Will Give Brooklyn Batter Baseball With Injection of New Ideas". Reading Eagle. Retrieved November 4, 2014 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ Cuddy, Jack (January 25, 1932). "Max Carey Intends To Build Robins Around Hack Wilson". The Pittsburgh Press. UP. Retrieved November 4, 2014 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ Carroll, Ed (March 24, 1932). "Sportalk". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved November 4, 2014 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ "Flatbush Betting 5 to 1 Max Carey Gets The Ax". The Pittsburgh Press. UP. February 20, 1934. Retrieved November 4, 2014 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ "Brookly Dismisses Max Carey As Manager". The Pittsburgh Press. February 21, 1934. Retrieved November 7, 2014 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ a b "Carey, Max". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- ^ "Max Carey". All-American Girls Professional Baseball League Players Association. Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- ^ a b "Carey top base-thief of his day". The Morning Record. AP. June 1, 1976. Retrieved November 7, 2014 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Tommy (January 30, 1961). "Dream Comes True, Carey Reaches 'Hall'". The Miami News. Retrieved October 29, 2017 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Hesser, Charles (July 19, 1968). "Citrus Tycoon Griffin In Town For Wallace". The Miami News. Retrieved October 29, 2017 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Two Ex-Outfielders Enter Hall Of Fame". The Palm Beach Post. AP. January 30, 1961. Retrieved October 29, 2017 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Max Carey Succcumbs". The Evening Independent. AP. May 31, 1976. Retrieved November 4, 2014 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ Ferguson, Harry (May 28, 1963). "Big Ideas Copied; Even Lillian Russell Got Into The Act". The Pittsburgh Press. UPI. Retrieved November 7, 2014 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ "Patents Granted". The Pittsburgh Press. September 10, 1927. Retrieved November 7, 2014 – via Google News Archive Search.

Further reading

- Bennett, John. "Max Carey". SABR.

External links

- Max Carey at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics from MLB · ESPN · Baseball Reference · Fangraphs · Baseball Reference (Minors) · Retrosheet · Baseball Almanac

- Max Carey managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com

- Max Carey at Find a Grave

Fact Sheet

- Wondering what Max Carey (MLB)'s real name is? Max Carey (MLB)'s real name is Maximillian George Carnarius

- Max Carey (MLB)'s nationality is American

- Max Carey (MLB) works as a(n) professional baseball player

- Max Carey (MLB) was born on 1890-1-11

- How old is Max Carey (MLB)? Max Carey (MLB) is 136 years old

- Is Max Carey (MLB) single or married? Max Carey (MLB) is Married (Aurelia Behrens)!

- Where did Max Carey (MLB) go to school? Max Carey (MLB) is a graduate of Concordia College

- Max Carey (MLB) has 2 child/children

FAQ

Tags: Max Carey (MLB) net worth 2026, 2026 net worth Max Carey (MLB) 2026, what is the 2026 net worth of Max Carey (MLB) , what is Max Carey (MLB) net worth 2026, how rich is Max Carey (MLB) 2026, Max Carey (MLB) wealth 2026, how wealthy is Max Carey (MLB) 2026, Max Carey (MLB) valuation 2026, how much money does Max Carey (MLB) make 2026, Max Carey (MLB) income 2026, Max Carey (MLB) revenue 2026, Max Carey (MLB) salary 2026, Max Carey (MLB) annual income 2026, Max Carey (MLB) annual revenue 2026, Max Carey (MLB) annual salary 2026, Max Carey (MLB) monthly income 2026, Max Carey (MLB) monthly revenue 2026, Max Carey (MLB) monthly salary 2026